The Worst Deal in History: Why Mining Has Ransacked Australia While the Press Looked Away

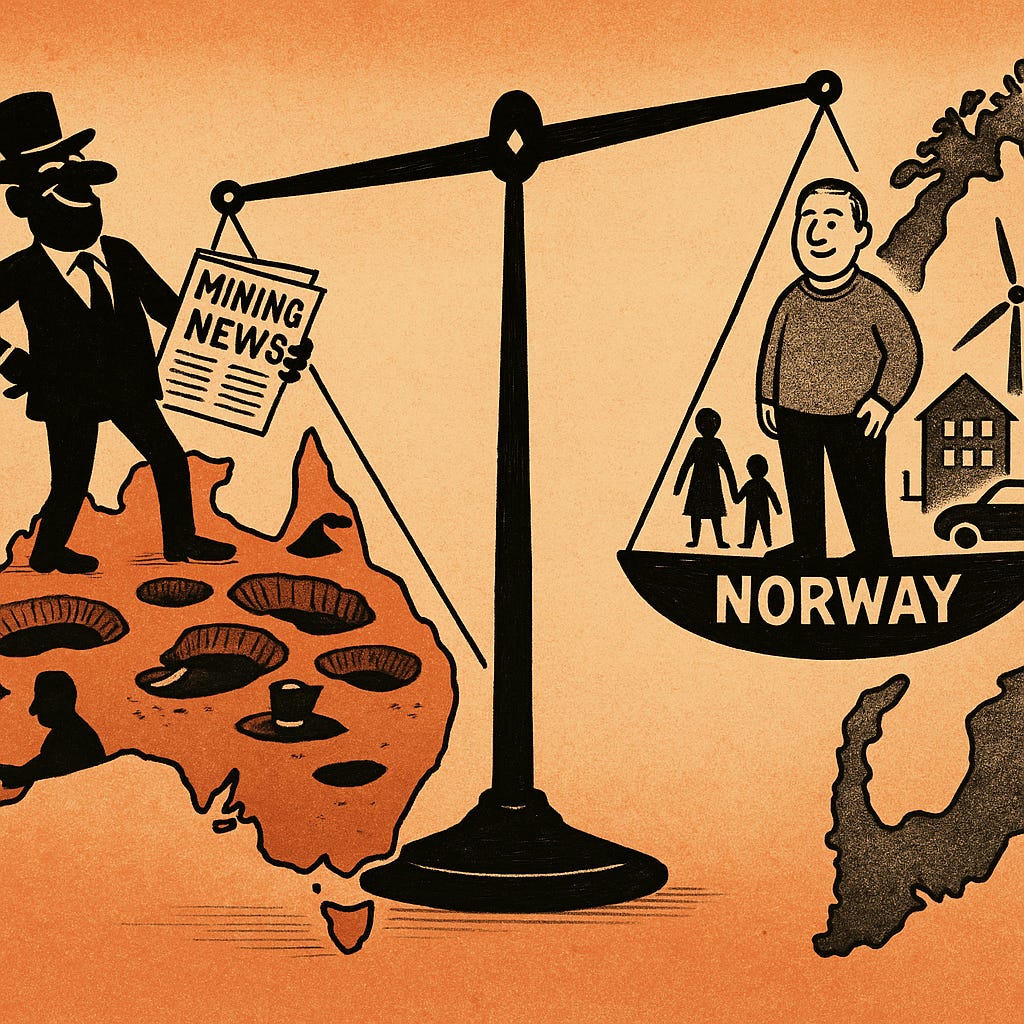

The Road Not Taken.

In 1972, Norway’s Parliament did what Australia never dared. They adopted a set of principles for developing oil that ought to be a global template. Unanimously, their MPs understood something Australia chose to ignore. When a finite resource sits under your soil, you own it. Sell it, by all means. But sell it wisely. Since 1996, they’ve taxed oil and gas company profits at seventy-six percent.

Norway established steep taxation on oil companies. They created Statoil, a state-owned enterprise that took 50 percent ownership of every new oilfield. The Norwegian Labour government, with cross-party support, ensured the public captured a genuine share of the wealth being extracted. A decade later, Nordic Council nations (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland) were running budget surpluses after their 1990s crises. They had learned something essential: taxing fossil fuels hard enables fair wealth distribution and funds social spending without hammering workers.

Today, Norway’s sovereign wealth fund sits at $1.8 trillion USD. Sweden has invested its resource wealth into universal healthcare, free tertiary education, and the world’s highest quality of life indices. Denmark powers its economy on renewable energy funded by decades of sensible resource taxation.

Australia handed over the shop keys and asked if they’d remember us in the thank-you notes.

The Numbers That Should Shame Us

Let us be precise about the arithmetic of surrender.

Iron ore, Australia’s largest single resource export, pays royalties of just 7 percent of export value, while coal miners pay 8 percent. Both near the lowest in the world. Petroleum is worse. Petroleum products have generated $617 billion in exports since 2010. Of this, only $14.9 billion has been collected in royalties. An average rate of just 2 percent. Some gas companies, notably Shell and others, have paid no Australian tax in years despite selling hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of our gas.

The Minerals Council of Australia (speaking for the billionaires who now own this country’s subsoil) claims those rates compare well to Canada and the United States. They’re lying. At the time of the Future Tax System Review, Australia had more than 60 royalty schemes. Each state and territory administers its own arrangements, with different rates sometimes applying to the same commodity depending on whether it’s exported or sold domestically. That complexity isn’t accident. It’s baked in to obscure exactly how little we’re being paid and to prevent states comparing notes on being undersold.

At 2.5 to 7.5 percent ad valorem, Australia’s royalties are a sick joke. The 2009 Henry Tax Review explained why with blinding acuity: our royalty processes are rigged to miss the real profits mining companies are making. They are based on only a very small fraction of growth in private mining company profits. Nothing has changed since. By design. Self-interest rules.

But we foot the cleanup bill. Governments hold $10 billion in environmental bonds to help clean up when companies quit their sites. Another joke. These bonds won’t even begin to cover total rehabilitation costs in most cases. We get to pay the gap. This is the public’s insurance policy against the miners’ own recklessness. We’re insuring them against their own disasters. It’s another form of invisible subsidy.

The Pock-Marked Nation: What the Rip-Off Leaves Behind

Australia has around 80,000 abandoned mine sites. Cleaning up a large open-pit mine can cost hundreds of millions or several billion dollars. State departments and Auditors-General repeatedly warn that governments face rising costs as mining companies underfund their rehabilitation obligations. Without stronger regulation and properly secured bonds, taxpayers may ultimately shoulder billions in cleanup costs. The alternative is even more costly: a landscape of degraded ecosystems, polluted waterways, and abandoned pits left to future generations.

Queensland’s Commission of Audit, back in 2012, estimated that the state’s 15,000 abandoned mines represent a $1 billion liability. Nothing suggests that liability has shrunk. In WA alone, the disturbance footprint from mining is 138,203 hectares, with only 39,674 hectares under rehabilitation.

The Ranger Uranium Mine in the Northern Territory provides a window into what “rehabilitation” actually costs when it has to happen. Rehabilitation could cost between $1.6 and $2.2 billion. Why so steep? Environmental Requirements stipulate that tailings and contaminants must not result in detrimental environmental impacts for at least 10,000 years.

Let’s pause here. Reflect. We’re locked in to environmental supervision for longer than Western civilisation has existed. Why? Mining giants must extract uranium their way. They dictated the terms.

The Debit List: What Mining Has Actually Cost

Environmental and Ecological Damage

Exposure to agents released during mining operations (cadmium, iron, manganese, zinc, arsenic and lead) is associated with neoplastic and non-neoplastic diseases in adults and children. Lead mining is specifically associated with negative fertility effects in men and intellectual disability and impaired immune function in children. Asbestos mining is associated with higher morbidity and mortality due to respiratory and non-respiratory cancers. Whilst asbestos mining was discontinued in 1983, 700 to 900 Australians continue to die from mesothelioma each year. That’s two people every day.

Water systems have been systematically poisoned. Australia’s three largest emitting coal mines (located in Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland) are seeping the combined CO2 equivalent of around 30,000 cars annually. The clean-up will take decades. The pollution will persist for millennia.

Mining workforce deaths are 3.4 per hundred or nine worker fatalities annually, ranking it third among all Australian industries for fatality rates. Workers risk death or serious injury. Daily. Yet despite its manifold harms, we are taught that mining is our guardian angel.

The Social and Human Cost

The Yindjibarndi Aboriginal group filed a landmark case claiming $1.1 billion in damages over mining activities on their land. Claims include $1 billion in compensation for cultural damage caused by a mining project and $678 million for economic losses. The Solomon mine, operated by Fortescue, has damaged more than 285 significant archaeological sites and six Dreaming or creation story tracks. Sacred knowledge passed down through generations over 40,000 to 45,000 years of human settlement.

Communities have been gutted. Regional towns built on mining look on as profits vanish, jobs evaporate, and local economies collapse into addiction, unemployment, and family disintegration.

Residential properties located within two kilometres of large open-pit gold mines trade at a 20 to 30 percent discount to similar properties six to seven kilometres away. That’s the capitalised cost of living next to someone else’s wealth extraction machine.

The Economic Betrayal

And here’s the bitter irony. Mining isn’t even the economic engine Australia pretends it is. The mining industry’s claims of economic contribution have been inflated by combining royalties with company tax payments into a single figure. This vastly inflates the contribution of the mining industry to the Australian economy and government revenue.

Mining contributes less than 10 percent to GDP. Less. The mining billionaires have convinced the nation that we’re dependent on them when the dependency runs the other direction.

The Captured State: Western Australia and the Names We Should Know

Western Australia is the textbook example of regulatory capture.

In Western Australia’s iron ore industry, BHP Billiton operates the Mount Whaleback mine (the biggest single open-pit iron ore mine in the world) while Rio Tinto operates many Pilbara mines connected by huge private rail networks. Fortescue Metals Group, where Andrew Forrest holds a 36.25 percent controlling stake worth over $2 million daily in dividends since 2011, has accumulated over 93,000 square kilometres of mining tenements. Three times the combined holdings of Rio Tinto and BHP.

The WA government rolled over. State Agreement Acts carved out special treatment for these companies. Access to rail networks by third parties is governed by the State Agreements Act, while other mines either connect to state government-owned railways or truck their ore to loading points. The major miners own the infrastructure. They set the rules. They use that power ruthlessly, as the Yindjibarndi case demonstrates.

When Yindjibarndi leaders asked Fortescue for a 2.5 percent royalty payment as compensation for mining on their land (a rate Rio Tinto pays to Hancock Prospecting for similar arrangements), Fortescue refused, offering only 1 percent of the $5 billion in annual revenue its mine was expected to generate. Fortescue then launched a decade-long war of attrition, including a failed attempt to revoke their legal control over the land.

Rio Tinto and BHP operate with similar arrogance. They’re not there to serve the community. They’re there to serve themselves: they’ve bought the government to prove it.

The Press: How a Corporate Press Built a Myth

Now for the collusion that makes all this possible.

Australia’s media landscape is so concentrated that only Egypt and China have less diverse ownership. News Limited was established in 1923 by James Edward Davidson and funded by the Collins Group mining empire for the express purpose of publishing anti-union propaganda when he purchased the Broken Hill Barrier Miner and the Port Pirie Recorder. Following Keith Murdoch’s acquisition of a minority interest in 1949 and his death in 1952, his son Rupert Murdoch inherited The News, described as the “foundation stone” of News Limited.

Let that history sit: the corporate media in Australia was literally born as a tool to suppress working-class resistance to mining corporate power.

Today, News Corp owns two-thirds of the country’s metropolitan print mastheads and some of Australia’s most popular news websites, with radio interests in every state and territory, along with a majority share of the Foxtel news network which broadcasts Sky News. Murdoch is a foreign citizen exercising extraordinary power over what Australians are permitted to think about their own country.

How does this translate into mining coverage? Through several interlocking mechanisms.

First, advertising dependency. Classified advertising has largely moved to non-media companies, leading to increased reliance on consumer advertising as the chief revenue source. This directly threatens editorial impartiality. Major advertising spenders whose interests align with mining corporate power face no real scrutiny from major newspapers.

Second, editorial capture. Both Murdoch and mining billionaire Gina Rinehart bring overarching political ideologies to their newspapers. Murdoch was an early supporter of “small government”, low tax, deregulation and privatisation. Rinehart is a passionate opponent of new taxes for the mining industry. Owners choose editors. Editors choose stories. Stories shape what the nation believes.

Third, the myth-making itself. News Corp began its corporate life in 1922 as News Limited, secretly established by a mining company owned by the most powerful industrialists of the day, and was created for the express purpose of disseminating “propaganda”. That DNA hasn’t changed. The mining narrative (that mining “keeps the lights on,” that mining companies are “job creators,” that questioning mining is questioning Australia’s future) has been repeated so often by the corporate press that it’s become invisible orthodoxy.

The result? Murdoch papers have launched campaigns against climate action, defended mining expansion, and attacked anyone questioning mining’s real contribution to the economy. They’ve done this while taking advertising from the mining companies themselves. The circle is complete. Mining pays to advertise in papers owned by people who depend on the mining industry’s political dominance to protect their fortunes.

The Melbourne Cup stops the nation for a day. No one stops to ask why we’re surrendering our mineral wealth at 2 percent royalties while Norway collects 78 percent.

The Myth at the Centre

For decades, Australians have been told that mining “keeps the lights on.”

It’s nonsense. Mining contributes less than ten percent to GDP, yet the industry has convinced the nation that the country is dependent on mining when the dependency arguably runs the other direction. The lights stay on because of energy networks, not because Rio Tinto exists.

The myth serves a purpose. It seeks to justify the surrender of public wealth, the poisoning of the land, the abandonment of communities, and the refusal to tax mining companies at rates that would allow the public to benefit from its own resources.

Meanwhile, abandoned mines pile up. One hundred billion dollars’ worth of restoration liability sitting on Australian taxpayers’ shoulders while mining billionaires count their dividends and the press prints their press releases uncritically.

What We Could Have Had

Norway provides the counter-example. Since 2000, the Nordic economies grew 28 percent while carbon dioxide emissions fell by 18 percent. The Nordic countries established what Australia never did: the will to say no. To say our minerals belong to us. To say the billionaires don’t get to write the rules.

Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland taxed fossil fuels hard and built the world’s most prosperous, equitable societies. We have better mineral wealth than most of them. We have the democratic machinery. We have the evidence.

What we lack is the spine.

The Time for Surrender is Over

The miners will scream. The captured press will print their talking points. The Minerals Council will commission studies proving that apocalypse awaits if we tax them fairly. They will deploy every lever of power they’ve accumulated over a century.

Let them scream.

The numbers are clear. The players are named. The complicity is documented. The Nordic example proves there was another path. We chose the wrong one. But we didn’t have to. And we don’t have to keep choosing it.

What we need is the spine to reject a century-old deal that was rotten from the start.